Tignes, the village they drowned

This year, 2022, marks the 70th anniversary of the disappearance of Tignes. “But wait a minute! Tignes is a world-famous ski resort,” you may retort. Yes, but before it was a ski resort, it was a village in a different valley and its tragic story remains a painful collective memory in the Tarentaise region of Savoie, France.

Like many of France’s iconic ski resorts, Tignes was custom-built in the mid-1960s as part of the French government’s great 1964-1977 “snow plan” to build modern, functional ski resorts at high altitudes. But unlike many of its sister resorts, Tignes existed long before it became a resort. It was a settlement scattered along the banks of the Isère river in a basin-like valley at 1,700m altitude. The Isère snakes southeast through the narrow gorge of Val d'Isère and northwest through two large rocky outcrops... ideal as an anchor for a hydroelectric dam.

The project, first mooted in 1929, was delayed first by the economic crisis of the 1930s, and then by World War II. Finally launched on 10 May 1946, France’s highest dam (181 m) created a 235 million cubic metre artificial lake, the Lac du Chevril, covering an area of 270 ha. Today, it produces all the electricity needed by the city of Grenoble. But this came at the cost of drowning Tignes.

The 473 villagers fiercely opposed the project, resorting to sabotage and lying down in the path of trucks trying to access the site in order to draw the attention of journalists. As a result, the village became a household name in France and came to symbolise the difficult balance between tradition and modernity.

Despite their efforts, the dam was built, and floodgates were closed on 15 March 1952. But the villagers wouldn’t budge. Few had accepted the EDF electricity company’s offers of compensation, preferring to stay in the village. So first their telephone wires were cut on 3 March. Then, with water rising a metre a day, 300 policemen arrived before dawn on 17 March to occupy strategic points in the village, including the bell tower so the tocsin could not be sounded! With water lapping at their doorsteps, families were left with no choice but to leave. On 13 April 1952, Easter Sunday, the last mass was held in the church whose bells were already being melted down to cast six bells for the new St Jacques church in Boisses on a plateau at the western end of the dam. It is an exact replica of the original church.

The cemetery was emptied and together with the dismantled war memorial, the coffins were taken to Boisses as were furnishings from the church, the school, and the city hall. And then all the buildings in Tignes were dynamited to prevent Tignards from trying to move back into their homes when the Lac de Chevril was emptied every 10 years or so to allow for inspection of the dam. But the ruins were visible “just long enough to re-open our wounds” as José Reymond writes in Tignes, mon village englouti. It will not be emptied again as the dam can now be inspected by underwater robots.

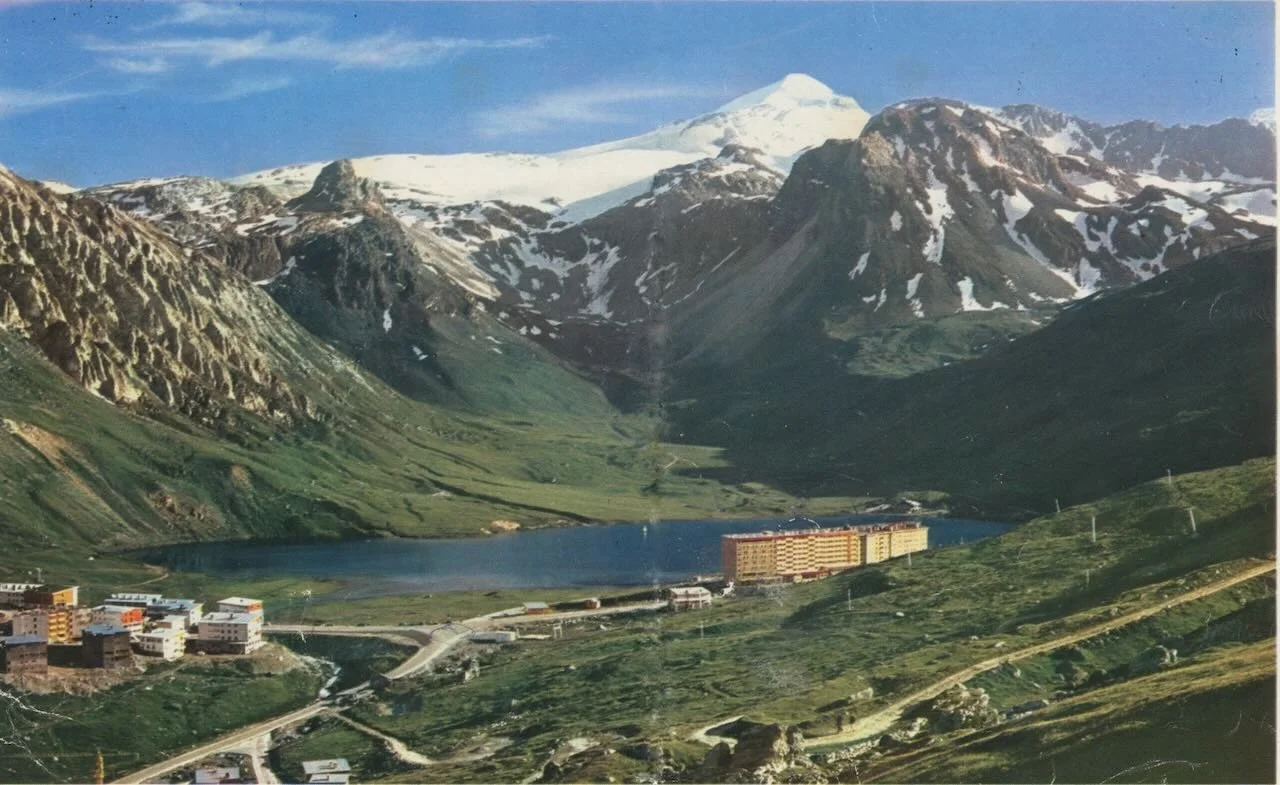

Only 15 Tignard families out of 87 stayed in the region: the others dispersed. When construction of the ski resort began in 1952 on the shores of a natural lake, the Lac de Tignes, at an altitude of 2,100 m, these 15 families were given priority to buy land there. But few did so, unable to imagine living year-round at such a high altitude, and uninterested in joining the tourism industry.

The only building up there was a shepherd’s refuge built in 1925. It’s still there! The villagers who stayed chose architect Raymond Pantz over a government-appointed architect to design their new village because he had bought land there in the 1930s and even had a private ski lift! Pantz built the new village at the eastern end of the Lac de Tignes and the 10 seven-storey high buildings, built between 1956 and 1974, were put on the northern shore of the lake. In 1968, Pantz designed Val Claret at the southwestern end of the lake, at the foot of the ski lifts that serve the Grande Motte glacier.

Twenty years ago, a statue by Livio Benedetti was finally erected in memory of the old village of Tignes. Bizarrely, “La Sarrazine” stands 3.80 m tall by the Lac du Chevril on the road to Val d’Isère looking out to where the old village of Tignes used to be and is nowhere near the road that actually goes up to where Tignes is today. But if you look to your left across the lake just before you drive through the only tunnel en route from Tignes 1800 to Tignes 2100 you just might make her out.