Discovering the treasures of Troyes

Troyes (pronounce trwa), in the Aube department, east of Paris, is somewhere I could quite happily live. And barring that, it’s somewhere I love to visit.

It has Gothic churches and museums galore, the greatest collection of half-timbered houses in the country, more than its fair share of world-class stained-glass, a dynamic, well-maintained and agreeable city centre, the largest factory outlet in Europe, and three huge lakes within less than an hour’s drive which offer everything a seaside resort would with the added advantage of millions of birds who stop here for a bit of rest and recuperation on their migration routes.

Oh, and of course, the Aube department is second only to its northern neighbour, the Marne, for quantities of Champagne produced!

So clearly, not a town to visit in one day. But a long weekend might do, perhaps visiting a couple of religious edifices and one museum per day otherwise you’ll suffer from an indigestion of stained-glass, Gothic architecture and handheld tools! Not to mention the local delicacy “andouillette” (chitterling sausage) which I’ve never tried after realising it took my husband at least two days to digest one! I prefer a glass of bubbly.

Troyes has had its share of disasters: in 888 the Vikings burnt it down, in July 1188 the cathedral and other important buildings were reduced to ashes and in May 1209 large segments of the town went up in flames. But the worst of all was a catastrophic two-day fire in May 1524 that destroyed 1,500 houses, about a quarter of the city. Most of the damage was in the most affluent merchants’ neighbourhood. Those who could afford to rebuild in stone did so, but the others had to replicate the medieval design of their previous home.

So although it looks medieval, the historic city centre we see today is largely post 1524 so is in fact Renaissance.

Last century Troyes was left almost unscathed by WWII bombing campaigns but had become, to quote from tourist office document “an unattractive city with a serious image problem” adding it was a “genuine cesspool”!! So the most destitute neighbourhoods were pulled down and some of the city’s oldest timber-framed houses demolished. But fortunately, in the late 1950s/early 1960s some locals decided to save whatever they could and founded the Association de Sauvegarde du Vieux Troyes, today renamed Sauvegarde et Avenir de Troyes. Over the past 70 years its volunteers have convinced successive local governments to restore the city to its former glory.

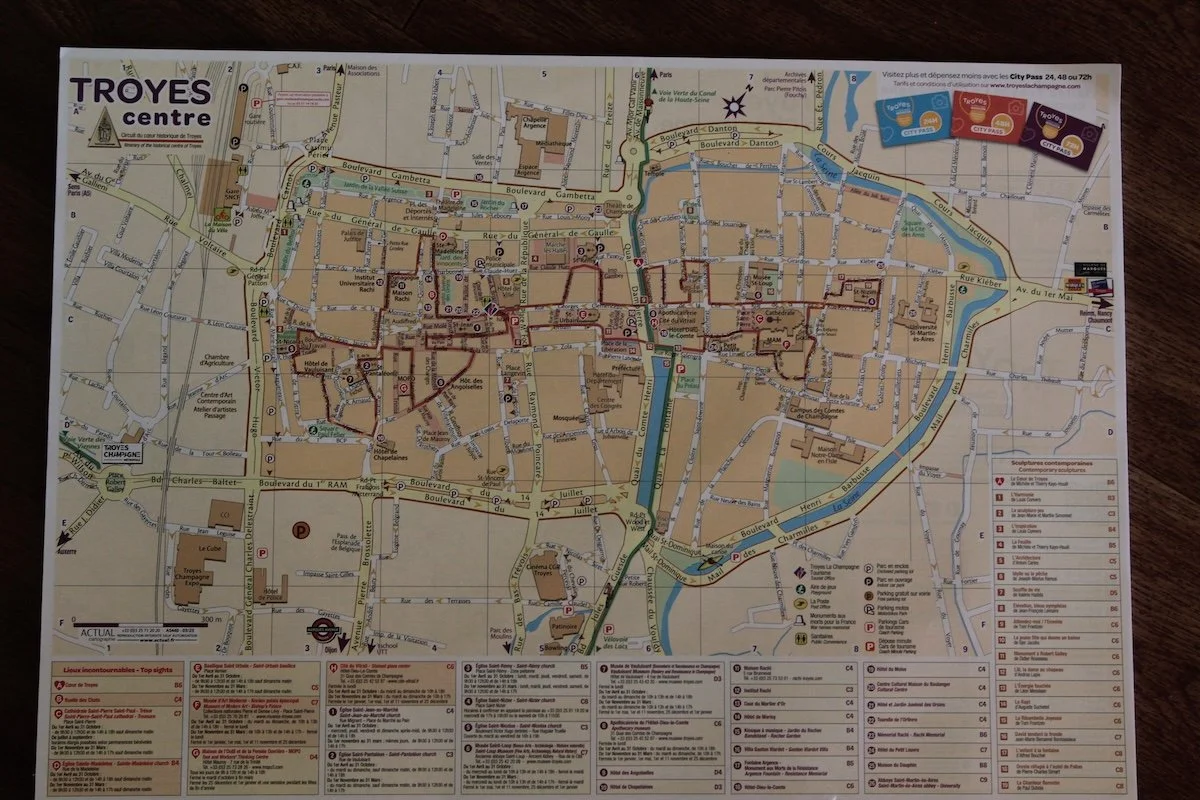

And glorious it is! The historic city centre is referred to locally as “Le Bouchon” (the cork) because, although it pre-dates the invention of Champagne wine by more than a thousand years, it is shaped like a Champagne cork lying on its side with the head, fashioned by the Seine, facing east. A canal with fountains slices the cork north to south. West of this canal the parallel sides of the cork’s body lie where the ancient city walls used to be.

Thankfully Le Bouchon is small (2 km from east to west and 820m north to south), so there’s no need for a car. I leave mine in the large (and free!) outdoor car park in front of Le Cube, the exhibition centre just beyond the south-west corner of Le Bouchon.

I love just meandering along the cobbled, pedestrian streets admiring the colourful, medieval, half-timbered houses, all leaning hither and thither. I’m amused by the Maison des Chanoines on the corner of the rue Émile Zola (the main pedestrianised shopping street) and the rue Turenne. The original front door now finds itself uselessly on the first floor because the house was moved here in 1969 but reconstructed on a modern, concrete ground floor to align its roof with others in the street. I’m told it’s easy to move half-timbered houses as long as you make sure you number all the beams and put them back up in the right order!

Many guidebooks encourage a visit to the narrowest street, the “ruelle des chats” (cat street). Nothing to do with cats, apparently, but an ancient misspelling. It should have been the “ruelle des chas” (eye of a needle street) which is much more appropriate! Personally, I find it over-rated.

Underrated, on the other hand, is the extraordinary Saint Pantaléon church (where the local Polish community worships), remarkable for three things: height, light and statues.

Because the nave is narrow, it makes the chestnut-wood barrel-vaulted ceiling which rises 28m (92ft) seem immensely high. The glass windows, decorated with grisaille paintings, fill the 17th century top half of the nave allowing light to flood inside the building giving an impression of weightlessness. But its most extraordinary feature is the abundant population of statues, most not sculpted for this church but rehoused here after the French Revolution. Their sheer number means they’ve been arranged in two rows on the walls so you get a much closer view of those on the bottom row than is generally the case. Others are on the floor so you can look them in the eye.

On my last visit, on a freezing cold day (the temperature outside was -5°C and the temperature inside possibly a little colder!) the keeper in his tiny, heated glass kiosk very kindly lent me his guide to the statues and it was invaluable. I don’t know why more of the information it contained isn’t in the free pamphlet that’s available.

Saint-Pantaléon is one of seven remarkable churches in Le Bouchon, that’s one church for every 250m2 of the city centre!

I love the atypical open-air belfry of the Saint-Jean-au-marché church where King Henry V of England married Catherine of France, but haven’t yet been inside. Instead I generally head towards Troyes’ oldest church, Sainte Madeleine, which contains one of only 21 rood-screens in France. This early 16th century stone partition between the chancel and the nave drips with intricate, flamboyant sculptures that were all polychrome until they were whitened in the 18th century.

Further along, squeezing through the ruelle des chats, one reaches Saint-Urbain basilica. After serving as a grain silo and then a general store during the French Revolution, it has now resumed its place as a jewel of Gothic architecture, often compared to the Sainte Chapelle in Paris because of its vast expanses of stained-glass. My rough estimate is that 5/6ths of the choir structure is made up of stained-glass so on a sunny day the stone walls and pillars sparkle with colours. It’s just gorgeous.

From the basilica it’s a short walk to the Saint Peter and Saint Paul cathedral across the Trévois canal where I’m always amused by the modern sculpture group of a dog who’s jumped through the bridge railings to chase geese who are flying off. On the way one passes the Hôtel-Dieu-le-Comte, a hospital from the XIIth Century until 1988, which today houses the Apothecary Museum and the Cité du Vitrail (stained-glass city) which opened in mid-December 2022. Here, instead of straining your neck to look up at the stained-glass as in a church, you are at eye-level with it so can admire the skill that goes into making these works of art. You also learn how stained-glass has been made over the centuries and restoration procedures. It’s all fascinating.

The single-towered (because money ran out to build the second one!) Saint Peter and Saint Paul cathedral has an absolutely stunning 1,500 m2 of stained glass windows, amongst the most remarkable in France. Here too on a sunny day the colours reverberate onto the light Burgundy stone of the soaring Gothic pillars that rise to create a vault 29.5m high.

Just alongside the cathedral is the Modern Art Museum, reopened in 2022 after a four-year renovation. It was created in 1982 to house the extraordinary collection of Pierre and Denise Lévy who made a fortune in the textile industry. They had discerning taste: Ernst, Dufy, Millet, Rodin, Degas, Courbet, Gaugin, Matisse and Braque are just a few of the artists whose work is exhibited. There a particularly interesting work by Robert Delaunay which is noticeable because there’s a mirror behind. A restorer working to consolidate a tear in 2019 on the back of a large oil painting “Les Coureurs” (one of eight Delaunay painted for the 1924 Paris Olympics) noticed after removing the canvas’ protective backing that the canvas itself had been whitewashed. Once this was removed a finished portrait of Bella Chagall was revealed. You can see it in the mirror.

But to me an even more interesting discovery was the Maison de l’outil et de la pensée ouvrière (Tools and trades museum). Now I am not particularly skilled in DIY nor particularly interested in tools but am nevertheless enchanted by the museography.

It takes incredible imagination to display in an interesting, engaging and visually pleasing manner more than 12,000 handmade tools from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. But here the museographers have pulled it off. The tools are beautifully showcased in 65 displays organised by theme and divided into four families: wood, iron, animal and mineral. If you look at the hammers, for example, you realise that they are displayed as though in a stop-motion analysis of the movement an arm would make holding a hammer! Explanatory panels in the museum are in French but I loved the excellent audio guide in English (and other languages) which gives an overall introduction to the showcase in one voice, and a second voice then gives details on a number of the tools on display. I tended to skip this second voice because sadly I didn’t have two hours to spare as I’d already been around the museum once before I discovered the audio guide!

Many visitors to Troyes come here first to visit the modern equivalent of the religious edifice: the shopping centre! From the 12th century Troyes inhabitants have been weavers, drapers, dyers and launderers and the city became a European centre of excellence in the manufacture of hosiery (bonneterie in French). At its peak in 1970 the industry employed 24,397 and monopolised the French knitwear and hosiery sectors: stockings, socks, underwear, polos, and world-famous brands such as Lacoste and Petit-Bateau were founded and still manufacture here.

Imperfect items were sold to employees at much reduced prices and then in the 1960s somebody had the idea of creating a centre where all these seconds could be sold in one place and hey presto: the factory outlet was born! Today there are four factory outlet zones around Troyes with a total of 148 shops.